(In which I try to give you online drawing lessons courtesy of a novel.)

***

So I haven’t written for weeks. And I thought I dedicated myself in posting a new entry per week. As if these were not enough, I haven’t finished reading Hickey yet. And to compensate for the display of abandoning myself to procrastination, I am writing an online lecture on what to expect and do on the first day of a painting/drawing lesson. And please pardon me for the sporadic interruptions brought about by my stream of consciousness.

“Here’s what we need”, he said brightly, holding up a piece of charcoal he dug from the bottom of the box.

“I brought pencils,” I said, showing him the brand-new tin case.

“It’s too early for pencils,” he said. “Charcoal first, then pencils.”

Looking back to all those years I’ve learned how to draw, I never remembered using charcoal. It seems like it has become a specially separated lesson on drawing and not a part of a series of medium. My other classmates who, back then, studied portraiture, used charcoals after we all learned how to shade with our Hs, HBs and Bs. Because the main sequence is that it should be pencils first before colors.

Looking back to all those years I’ve learned how to draw, I never remembered using charcoal. It seems like it has become a specially separated lesson on drawing and not a part of a series of medium. My other classmates who, back then, studied portraiture, used charcoals after we all learned how to shade with our Hs, HBs and Bs. Because the main sequence is that it should be pencils first before colors. The first thing I have drawn upon entering an art school was . . . my left hand – which I think is more interesting than a brick. Not that I am questioning the author’s or Klimt’s idea of a first subject. I just thought that trying to draw your own hand is an exercise that connects you to yourself. It’s more challenging even, to force an artist to look deeper and make sure he’s going to see his own hand on the paper after thirty minutes.“Are you ready?” said Klimt.

“But where’s the easel?” I asked in surprise.

“Today, we’ll sit at the table,” said Klimt. He swept the red cloth aside. Mrs. Klimt took it up, folded it and put it on her lap. Then he taped a sheet of paper to the table and pulled a brick out of the toolbox. I tried to guess what the brick might be for. To keep the paper from blowing away? To sharpen the chalk? He placed the brick in front of me stood with his arms folded. I waited.

“Well,” he said. He looked at me expectantly. . .

“Well what?

“Draw”

“I don’t understand,” I said. “What am I supposed to draw?”

He nodded toward the brick.

Somehow this approach amazed me. Giving a definition of the subject and forgetting it abruptly means to remove all subjectivity or objectivity influenced by its denotation means having to look at an object without bias. If that was my first lesson, how would I define my hands?“Draw the brick?” I said incredulously.

“That’s right,” he said. “Draw the brick.”

“But that’s just . . . a brick.” I knew I sounded like an idiot.

“And what is a brick? He said. He sounded like he was teaching a very young child. Was it a joke? But he was waiting.

“I don’t know, clay that’s baked in an oven . . .”

“Stoneware is baked in an oven, too, but you wouldn’t confuse a pitcher with this brick, now, would you?

This wasn’t how a drawing lesson was supposed to go. I should have been sketching a bowl of fruit, or some bottles, like we used to do in school with out art teaches. I didn’t know how to respond. “No, sir,” I said.

He laughed. “I know you think I’m insane,” he said, ”but this was my very first lesson in art school when I was eleven, and it will be yours. Try to give me a better definition. It won’t hurt.”

I took a deep breath. “A brick is a rectangular piece of clay that is fired in an oven and used as a building material.”

“Excellent. Now forget all that we’ve said and draw what you see.”

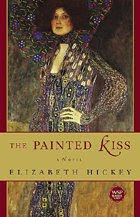

Photo Source: